The first film to pair director Don Siegel and Clint Eastwood was the 1968 release "Coogan's Bluff." They would go on to make six films together including the film that made Eastwood a superstar "Dirty Harry." Eastwood's directing style is also largely indebted to Siegal. Both men like to shot at a fast pace, trusting their instincts and their collaborators. In some ways,the character of Arizona Deputy Sheriff Walt Coogan is a prototype for Harry Callahan, they share a ask questions later take on police work and sneering dislike for big-city bureaucracy, but this is a lighter picture.

The film gets most of its comedic mileage from its fish-out-of-water elements, whether Coogan is encountering cheating taxi drivers, big-city tough guys, or goofy hippies. The NYC police are primarily represented by Lee J. Cobb's hard-nosed Lt. McElroy, and while his character is a bit of a stereotype, he manages to imbue it with some personality. Susan Clark provides the requisite romantic interest as probation officer Julie Roth, and while some of their interludes are a little on the dull side, she is a bit of a spark plug who puts an interesting spin on her dialogue.

Action sequences are solid, with a spirited, messy pool hall fight and a motorcycle chase as highlights. Its impressions of the hippie scene, on the other hand, feel more than a little out of touch - like a forty-something screenwriter's idea of what a hippie club would be like. "Coogan's Bluff" is a flawed, minor Eastwood picture, but still interesting, primarily for its place in his iconography; we see him tinkering with his image, moving away from the cowboy image of his television work and Spaghetti westerns and into a more brutal, urban landscape.Plus it points to great things in store for the Siegel/Eastwood combination.

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Friday, January 21, 2011

Spaghetti Western comes to America

"Hang 'Em High" holds an important place in Clint Eastwood's career. Not only was it the first film to be produced by his production company, Malpaso, but it was the first American film in which he received top billing. Released in Summer 1968, it rode the popular wave of Sergio Leone's Man with no Name trilogy with Eastwood, and demonstrated the influence that Leone's films had exerted on the Western genre. The plot is a old Western standard of revenge, but it feels pedestrian and plods along providing little entertainment for long stretches of time.

Most of the film is pretty predictable - Eastwood sets out as a vigilante but becomes a man of the law and develops a conscience along the way. There is a half developed rape revenge subplot that features actress Inger Stevens but that seems to have been included so there would be a female presence in the film. Director, Ted Post (who worked with Eastwood on the television series "Rawhide" and collaborate with him again on the Dirty Harry sequel "Magnum Force") works in anonymous fashion, aping Leone's use of the zoom lens and keeping the whole affair moving forward.

Eastwood's character may not be a "man with no name" of course, but he is decidedly vicious, single minded and not entirely sympathetic. This being Hollywood in the sixties, Eastwood's character is softened up and given a love interest. Unlike Leone's westerns Eastwood is surrounded by great character actors like Ben Johnson, Ed Begley and the ever reliable Pat Hingle. The film also features early work from Bruce Dern, already playing crazy, and Dennis Hopper, who dies too soon after only one insane monologue. The film was shot on beautiful locations, but doesn't look particularly impressive because of a bland cinematography and poor framing choices. The attitudes in the film are rather confused - it can't decide whether or not it is in favor of capital punishment, and some interesting observations about the development of Hanging Judges into State governments are left as something of an afterthought. There's also a certain gloating sadism that negates any serious thoughts the film has on the immorality of killing.

Most of the film is pretty predictable - Eastwood sets out as a vigilante but becomes a man of the law and develops a conscience along the way. There is a half developed rape revenge subplot that features actress Inger Stevens but that seems to have been included so there would be a female presence in the film. Director, Ted Post (who worked with Eastwood on the television series "Rawhide" and collaborate with him again on the Dirty Harry sequel "Magnum Force") works in anonymous fashion, aping Leone's use of the zoom lens and keeping the whole affair moving forward.

Eastwood's character may not be a "man with no name" of course, but he is decidedly vicious, single minded and not entirely sympathetic. This being Hollywood in the sixties, Eastwood's character is softened up and given a love interest. Unlike Leone's westerns Eastwood is surrounded by great character actors like Ben Johnson, Ed Begley and the ever reliable Pat Hingle. The film also features early work from Bruce Dern, already playing crazy, and Dennis Hopper, who dies too soon after only one insane monologue. The film was shot on beautiful locations, but doesn't look particularly impressive because of a bland cinematography and poor framing choices. The attitudes in the film are rather confused - it can't decide whether or not it is in favor of capital punishment, and some interesting observations about the development of Hanging Judges into State governments are left as something of an afterthought. There's also a certain gloating sadism that negates any serious thoughts the film has on the immorality of killing.

|

| Odd publicity shot of the cast |

Civil War Epic Ends the Trilogy on a High Note

Stylish, stylized, amoral, and brutally violent, Sergio Leone's final chapter of his Man With No Name Trilogy "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is a stunning, intoxicating masterpiece. Leone's depictions of a world full of rough, selfish individuals devoid of morality fascinate the viewer with its visual appeal. Leone shifts form extremely tight shots of his characters' eyes and harsh or terrified faces to sweeping, awe inspiring images of vast, barren landscapes. The actions of the characters moving through this emotionally charged world elaborately choreographed and perfectly timed like a dance. The director imbues every minute of the movie with a tangible, edgy excitement. He develops tremendous tension with his leisurely depictions of the film's characters performing various trivial actions, as bathing, checking a gun, or the like while violence looms in the immediate future. Then, punctuating such drawn out moments with the shocking brutality.

The director cannot, however, take sole credit for the film's success. For one thing, Ennio Morricone's score is consistently stunning and complements the movie throughout, evoking both wistful sadness and overwhelming excitement. It is surely among the most memorable pieces of music ever created for a movie and is familiar to first time viewers. The score of "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is as vibrant and alive as are any of the film's other qualities.

Finally, I should note that the performances of the three leads are truly wonderful. Clint Eastwood is cold and subtle as the nameless gunman known only as "Blondie." Lee Van Cleef endows Angel Eyes with a sadistic cruelty, and Eli Wallach gives life to the brutal, earthy, and some much needed comic relief Tuco. All add significantly to the movie's appeal. New to Leone's style is the humor throughout, particularly the uneasy alliance between the ‘good’ Blondie and the ‘ugly’ Tuco. But it’s pure gallows, with violence permeating the frame. The film is the rare third part of a trilogy that ends the series on a high note.

The director cannot, however, take sole credit for the film's success. For one thing, Ennio Morricone's score is consistently stunning and complements the movie throughout, evoking both wistful sadness and overwhelming excitement. It is surely among the most memorable pieces of music ever created for a movie and is familiar to first time viewers. The score of "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" is as vibrant and alive as are any of the film's other qualities.

Finally, I should note that the performances of the three leads are truly wonderful. Clint Eastwood is cold and subtle as the nameless gunman known only as "Blondie." Lee Van Cleef endows Angel Eyes with a sadistic cruelty, and Eli Wallach gives life to the brutal, earthy, and some much needed comic relief Tuco. All add significantly to the movie's appeal. New to Leone's style is the humor throughout, particularly the uneasy alliance between the ‘good’ Blondie and the ‘ugly’ Tuco. But it’s pure gallows, with violence permeating the frame. The film is the rare third part of a trilogy that ends the series on a high note.

Sunday, January 16, 2011

The Middle Child of the Man with No Name Trilogy

A sequel to "A Fistful of Dollars" seems like a foregone conclusion considering its worldwide success. But in 1964, there was nothing inevitable about it. Sergio Leone had received no financial compensation from the considerable box office of his first Western and wished to make a personal, partially autobiographical project about growing up in Trastevere during the 1930s. However, he was under pressure to repeat his Western success and Italian lawyer Alberto Grimaldi offered Leone 50% of the profits plus expenses. This was an offer that a man with a wife and children to support couldn't refuse. So he set out on the development of the ironically titled "For a Few Dollars More," wishing to top his earlier film. This determination shows in the finished product. "For a Few Dollars More" is a more ambitious film than its predecessor in terms of narrative, character and style and it's the film which really shows Leone developing the epic side of his filmmaking which would come to fruition in "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly." It may not be Leone's best film, but it may be his most purely enjoyable; an exercise in narrative filmmaking which brims with style and confidence.

Leone brings back the Man With No Name - this time briefly given the name Manco - in the shape of Clint Eastwood and explicitly makes him a bounty hunter (called bounty killers in the film) with no other motivation than money. This gives the film a specific historical context during the late 19th Century when law and order in the West was maintained in a decidedly fragile state by a haphazard system of local Sheriffs and traveling Judges. Bounty hunters were encouraged as an efficient way of finding and dealing with fugitives. Eastwood's all ready iconic character is joined by a new figure; Colonel Douglas Mortimer played the great character actor Lee Van Cleef. Mortimer is also a bounty hunter but one haunted both by his past as a soldier and a tragic family history. After a brief, witty confrontation , the two men team up with the common goal of bringing to justice El Indio (Volonte), a deranged, dope-addled bandit who is inextricably linked to Mortimer's family tragedy.

The sweeping confidence of the film reflects a director who is finally able to do what he wants in the way he wants. Leone's work is immensely stylish, packed with increasingly exotic use of close-ups and pacing which, while never slow, is a little stately in a manner which often recalls Luchino Visconti. There is more intentional humor in this film than in its predecessor with whole sequences built up for the sake of a humourous pay-off, such as the scene with the apples towards the end. There's a lushness to the film, both in its stunning visuals which make full use of the landscape in a way which Leone would intensify in his next two films, and in its emotional richness, largely supplied by the character of Colonel Mortimer. In "Fistful," there's not a great deal of motivation or even characterisation. In this film, Mortimer's character is all motivation and, partly due to Lee Van Cleef's sympathetic and witty portrayal, he comes across as the main target for our sympathy. Virtually every Spaghetti Western which followed the huge success of this movie in Italy would feature a flashback to explain the motivations of a particular character but few are either as simple or as effective as the one here. Leone keeps this in the background at first, with unexplained memory 'flashes' from El Indio that are later revealed as his connection with Mortimer. The pocket watch watch, with the initially unexplained portrait of a lady, is well used too, providing another angle of narrative suspense.

Everything in"For a Few Dollars More" seems a little bigger than in its predecessor. The violence is a little more graphic and sadistic, Carlo Simi's production design of El Paso - Leone's first great bustling period location - is on a larger scale and the psychopathic, sociopathic behaviour of El Indio is more melodramatic and theatrical. Gian Maria Volonte takes the opportunity to go over the top with both hands, consuming the scenery with relish as one of the nastiest, most irredeemable bad guys in cinema history. In contrast to this slightly garish conception, Clint Eastwood's performance seems all the more restrained and funny. He gets comic effects simply by doing very little and allowing all around him to emote their way into the stratosphere. His character is made even less heroic, again being the hero mostly because of his charisma and finally being slightly redeemed through his friendship with Mortimer. This friendship adds a more human dimension to the whole film, bringing in complex emotions which the first movie ignore. Leone originally wanted Lee Marvin for the role but couldn't afford the actor's asking price and Van Cleef's warm, likable performance is masterful; a mature, if cynical, reflection contrasted with Eastwood's youthful arrogance, even though Van Cleef was a mere five years older.

Leone's style is developing and the movie contains most of the elements which will be considered hallmarks of his film making. Along with the harshly cynical view of the world - good men have to turn to violence because of the greed and corruption around them - and extreme sclose-up shots, we get more religious iconography creeping in - the church in which El Indio delivers his speech about robbing the bank being an example - and the recurring motifs such as the circular dance of death during the final gunfight.All in all "Dollars is a worthy second film in an unintended trilogy with the best saved for last.

Leone brings back the Man With No Name - this time briefly given the name Manco - in the shape of Clint Eastwood and explicitly makes him a bounty hunter (called bounty killers in the film) with no other motivation than money. This gives the film a specific historical context during the late 19th Century when law and order in the West was maintained in a decidedly fragile state by a haphazard system of local Sheriffs and traveling Judges. Bounty hunters were encouraged as an efficient way of finding and dealing with fugitives. Eastwood's all ready iconic character is joined by a new figure; Colonel Douglas Mortimer played the great character actor Lee Van Cleef. Mortimer is also a bounty hunter but one haunted both by his past as a soldier and a tragic family history. After a brief, witty confrontation , the two men team up with the common goal of bringing to justice El Indio (Volonte), a deranged, dope-addled bandit who is inextricably linked to Mortimer's family tragedy.

The sweeping confidence of the film reflects a director who is finally able to do what he wants in the way he wants. Leone's work is immensely stylish, packed with increasingly exotic use of close-ups and pacing which, while never slow, is a little stately in a manner which often recalls Luchino Visconti. There is more intentional humor in this film than in its predecessor with whole sequences built up for the sake of a humourous pay-off, such as the scene with the apples towards the end. There's a lushness to the film, both in its stunning visuals which make full use of the landscape in a way which Leone would intensify in his next two films, and in its emotional richness, largely supplied by the character of Colonel Mortimer. In "Fistful," there's not a great deal of motivation or even characterisation. In this film, Mortimer's character is all motivation and, partly due to Lee Van Cleef's sympathetic and witty portrayal, he comes across as the main target for our sympathy. Virtually every Spaghetti Western which followed the huge success of this movie in Italy would feature a flashback to explain the motivations of a particular character but few are either as simple or as effective as the one here. Leone keeps this in the background at first, with unexplained memory 'flashes' from El Indio that are later revealed as his connection with Mortimer. The pocket watch watch, with the initially unexplained portrait of a lady, is well used too, providing another angle of narrative suspense.

Everything in"For a Few Dollars More" seems a little bigger than in its predecessor. The violence is a little more graphic and sadistic, Carlo Simi's production design of El Paso - Leone's first great bustling period location - is on a larger scale and the psychopathic, sociopathic behaviour of El Indio is more melodramatic and theatrical. Gian Maria Volonte takes the opportunity to go over the top with both hands, consuming the scenery with relish as one of the nastiest, most irredeemable bad guys in cinema history. In contrast to this slightly garish conception, Clint Eastwood's performance seems all the more restrained and funny. He gets comic effects simply by doing very little and allowing all around him to emote their way into the stratosphere. His character is made even less heroic, again being the hero mostly because of his charisma and finally being slightly redeemed through his friendship with Mortimer. This friendship adds a more human dimension to the whole film, bringing in complex emotions which the first movie ignore. Leone originally wanted Lee Marvin for the role but couldn't afford the actor's asking price and Van Cleef's warm, likable performance is masterful; a mature, if cynical, reflection contrasted with Eastwood's youthful arrogance, even though Van Cleef was a mere five years older.

Leone's style is developing and the movie contains most of the elements which will be considered hallmarks of his film making. Along with the harshly cynical view of the world - good men have to turn to violence because of the greed and corruption around them - and extreme sclose-up shots, we get more religious iconography creeping in - the church in which El Indio delivers his speech about robbing the bank being an example - and the recurring motifs such as the circular dance of death during the final gunfight.All in all "Dollars is a worthy second film in an unintended trilogy with the best saved for last.

The Birth of the Spaghetti Western

Although it wasn't the first Italian Western, Sergio Leone's "A Fistful of Dollars" was the film which introduced many of the conventions of the genre that would become known as the Spaghetti Western. The films which preceded it had been straight transpositions of the American style ; Leone's film broke with this tradition and the result is something which still has the exciting sense of a filmmaker discovering a whole new way of doing things. Over the course of his 'Dollars Trilogy' - comprising "A Fistful of Dollars,""For a Few Dollars More" and "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly," Leone and his collaborators created a sub-genre which went on to spawn countless imitations - both in Italy and elsewhere - and which had such an impact on the Western genre itself that the American films which followed it were never quite the same. That's a pretty damned impressive for an Italian film made in Spanish locations starring an American television actor for the equivalent of $200,000 during the spring of 1964.

The film is a loose remake of Akira Kurosawa's "Yojimbo" which is loosely based on Dashiell Hammett's novel "Red Harvest." Leone was fascinated by the cynical, shabby hero who seemed so removed from the American Western heroes portrayed by John Wayne, Randolph Scott, and Alan Ladd. There are so many important facets to Leone's first Western but I want to focus on the central figure of the film. What the audience sees is the traditionally heroic central character turned into something quite different. Clint Eastwood, who was playing Rowdy Yates on "Rawhide" and was contractually forbidden from appearing in American films during the show's hiatus could have easily played an upstanding, righteous man beset by evil men. But Leone wanted to do something different. In place of the usual Western hero - perhaps best represented by Alan Ladd in "Shane" or John Wayne in "Rio Bravo" - we have a morally ambivalent figure whose motives are considerably less pure than his counterparts. The Man With No Name watches cruelty without acting to stop it, shoots first without asking questions and brings down instant judgment upon anyone who tries him. If we find him heroic, it's mostly because he's more likeable than the incredibly unpleasant bad guys. The audience is expected to direct whatever sympathy towards Eastwood. After all, he's tough, a great shot, dependable and dryly funny, dispensing occasional quips such as the famous "Four coffins" gag towards the start. In this sense, as Christopher Frayling has pointed out, he's the model for the modern action hero; he can kill as many people as he wants because, ultimately, he's the only thing standing between us and complete moral anarchy. Later directors of Spaghetti westerns would push the audience over into the abyss in films like the spectacularly bleak, surreal cartoon violence of the Django series. However, Leone's use of the hero isn't the revolutionary break from convention as many critics have claimed it to be. The American Western was going in a more mature direction during the 1950s, there's a definite feeling that the hero figure was being gradually deconstructed in Anthony Mann's trilogy of Westerns starring Jimmy Stewart the hero is pushed away from the cliches into new psychological territory, making him increasingly dark, selfish and haunted by past sins. John Ford did something similar with John Wayne in "The Searchers" and Paul Newman's playing of Billy The Kid as a juvenile delinquent sadist in Arthur Penn's "The Left Handed Gun" points forward to the creation of a hero who is only removed from the villain by a few bullet holes. Moral ambiguity is everywhere in Leone's universe but it's also omnipresent in the work of Anthony Mann and Samuel Fuller. Indeed, you could hardly call John Ford's 1962 "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" a simple old-fashioned cowboy picture.

The next significant innovation is linked to the first and that's the use of violence. In American films, there was a rule imposed by the Production Code that you couldn't see a gun fired and a man fall down dead in the same frame. Leone throws this away in "A Fistful of Dollars", establishing the classic moments of the gun looming in the foreground and the men blown away in the background. Although the film isn't particularly explicit by his later standards, there's a brutality that very unlike anything in mainstream American film at the time. The gleeful sadism of the bad guys - laughing as they beat Eastwood - must have been profoundly shocking to those audiences whose idea of evil was Jack Palance in a black shirt.

Ennio Morricone's music, combining a vocal chorus with Fender Stratocaster guitar and orchestra, remains iconic and completely subverts stately epic conventions of Western scores by Elmer Bernstein and Alfred Newman. Future Westerns would imitate the score but never equal it.

"A Fistful of Dollars" remains, forty years on, cracking good entertainment. Leone's later films are more complex and ambiguous - there's nothing here to match the moral shadings of Colonel Mortimer or Cheyenne - but if it's a excellent piece of action film-making.

The film is a loose remake of Akira Kurosawa's "Yojimbo" which is loosely based on Dashiell Hammett's novel "Red Harvest." Leone was fascinated by the cynical, shabby hero who seemed so removed from the American Western heroes portrayed by John Wayne, Randolph Scott, and Alan Ladd. There are so many important facets to Leone's first Western but I want to focus on the central figure of the film. What the audience sees is the traditionally heroic central character turned into something quite different. Clint Eastwood, who was playing Rowdy Yates on "Rawhide" and was contractually forbidden from appearing in American films during the show's hiatus could have easily played an upstanding, righteous man beset by evil men. But Leone wanted to do something different. In place of the usual Western hero - perhaps best represented by Alan Ladd in "Shane" or John Wayne in "Rio Bravo" - we have a morally ambivalent figure whose motives are considerably less pure than his counterparts. The Man With No Name watches cruelty without acting to stop it, shoots first without asking questions and brings down instant judgment upon anyone who tries him. If we find him heroic, it's mostly because he's more likeable than the incredibly unpleasant bad guys. The audience is expected to direct whatever sympathy towards Eastwood. After all, he's tough, a great shot, dependable and dryly funny, dispensing occasional quips such as the famous "Four coffins" gag towards the start. In this sense, as Christopher Frayling has pointed out, he's the model for the modern action hero; he can kill as many people as he wants because, ultimately, he's the only thing standing between us and complete moral anarchy. Later directors of Spaghetti westerns would push the audience over into the abyss in films like the spectacularly bleak, surreal cartoon violence of the Django series. However, Leone's use of the hero isn't the revolutionary break from convention as many critics have claimed it to be. The American Western was going in a more mature direction during the 1950s, there's a definite feeling that the hero figure was being gradually deconstructed in Anthony Mann's trilogy of Westerns starring Jimmy Stewart the hero is pushed away from the cliches into new psychological territory, making him increasingly dark, selfish and haunted by past sins. John Ford did something similar with John Wayne in "The Searchers" and Paul Newman's playing of Billy The Kid as a juvenile delinquent sadist in Arthur Penn's "The Left Handed Gun" points forward to the creation of a hero who is only removed from the villain by a few bullet holes. Moral ambiguity is everywhere in Leone's universe but it's also omnipresent in the work of Anthony Mann and Samuel Fuller. Indeed, you could hardly call John Ford's 1962 "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" a simple old-fashioned cowboy picture.

The next significant innovation is linked to the first and that's the use of violence. In American films, there was a rule imposed by the Production Code that you couldn't see a gun fired and a man fall down dead in the same frame. Leone throws this away in "A Fistful of Dollars", establishing the classic moments of the gun looming in the foreground and the men blown away in the background. Although the film isn't particularly explicit by his later standards, there's a brutality that very unlike anything in mainstream American film at the time. The gleeful sadism of the bad guys - laughing as they beat Eastwood - must have been profoundly shocking to those audiences whose idea of evil was Jack Palance in a black shirt.

Ennio Morricone's music, combining a vocal chorus with Fender Stratocaster guitar and orchestra, remains iconic and completely subverts stately epic conventions of Western scores by Elmer Bernstein and Alfred Newman. Future Westerns would imitate the score but never equal it.

"A Fistful of Dollars" remains, forty years on, cracking good entertainment. Leone's later films are more complex and ambiguous - there's nothing here to match the moral shadings of Colonel Mortimer or Cheyenne - but if it's a excellent piece of action film-making.

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Determined Fighter

It has taken Mark Wahlberg five years to bring the underdog story of welterweight boxer Micky Ward to the screen in "The Fighter" and it was worth the wait. Originally set to star Wahlberg and Matt Damon under the direction of Darren Aronofsky until budget concerns derailed the production. So Damon was forced to drop out due to other film obligations and replaced by Brad Pitt. Pitt and Aronofsky leave the project when the budget is slashed in half. Wahlberg recruits David O. Russell who directed the actor in "Three Kings" and Christian Bale. All in all things couldn't have worked out better.

Russell, shooting almost entirely in Lowell on a fast 33-day schedule and tight $11 million budget, has made a boxing film that concerns itself not only with personal glory but with family feuds and crack addiction and delusion and the necessity of facing brutal truths and looking people you love in the eye and telling them they're history unless they clean up their act...this is what real families do, and why this movie feels so real every step of the way.

The acting is great from every player, especially from Bale (he's got the big showy part and is a lock for a supporting actor nod from the Academy) but also Wahlberg (he is the film's anchor,) Amy Adams (who is able to shed that goody two-shoes image she's been saddled with from her performances in "Junebug" and "Enchanted") and fierce Melissa Leo as the headstrong mother of Walhlberg, Bale and six of the grungtiest-looking blue-collar sisters you've ever seen in your life, let alone a film -- they all look like they've been eating chili dogs while knocking back shots of Jack Daniels since they were ten.

Ultimately, "The Fighter" moved beyond the cliches of the boxing genre. It is a film that could have been over-dramatized and heavy-handed had it been put in another director's hands, but Russell and his cast create a very specific atmosphere and set a particular mood that lends the film a sense of realism.

Russell, shooting almost entirely in Lowell on a fast 33-day schedule and tight $11 million budget, has made a boxing film that concerns itself not only with personal glory but with family feuds and crack addiction and delusion and the necessity of facing brutal truths and looking people you love in the eye and telling them they're history unless they clean up their act...this is what real families do, and why this movie feels so real every step of the way.

The acting is great from every player, especially from Bale (he's got the big showy part and is a lock for a supporting actor nod from the Academy) but also Wahlberg (he is the film's anchor,) Amy Adams (who is able to shed that goody two-shoes image she's been saddled with from her performances in "Junebug" and "Enchanted") and fierce Melissa Leo as the headstrong mother of Walhlberg, Bale and six of the grungtiest-looking blue-collar sisters you've ever seen in your life, let alone a film -- they all look like they've been eating chili dogs while knocking back shots of Jack Daniels since they were ten.

Ultimately, "The Fighter" moved beyond the cliches of the boxing genre. It is a film that could have been over-dramatized and heavy-handed had it been put in another director's hands, but Russell and his cast create a very specific atmosphere and set a particular mood that lends the film a sense of realism.

Wednesday, January 5, 2011

Do You Think It's all Right?

There are three plots at work in "The Kids Are All Right": a married couple hitting the rocks, two kids attempting to connect with their biological father, and a man coasting through his late 30s getting a major taste of adulthood. All of them are pretty good, unfortunately they feel like three different movies crammed into one.

The couple is Nic (Annette Bening) and Jules (Julianne Moore), who are preparing for the impending college-bound departure of their daughter Joni (Mia Wasikowska). Joni's younger brother, the oddly named Laser (Josh Hutcherson), is pressuring her (as an 18-year-old) to inquire about their biological father's contact information. She concedes, and the two meet up with Paul (Mark Ruffalo), the hippie-ish owner of an organic restaurant.

All five members of the cast are good (and Bening and Moore have some stand-out moments), although none of these veteran actors are stretching their talents. The screenplay, by Lisa Cholodenko (also the director) and Stuart Blumberg, can't shake the sensation that the viewer is watching a film that's been written and crafted in a certain way. As a director, Chodolenko's smart enough to get out of the way and allow the actors to carry the weight.

The movie is a pleasant, sometimes funny, occasionally moving experience that never seriously falters, but never adds up to anything special. It's not good, it's not bad, it's just sort of all right.

Plus the soundtrack does not feature the Who song of the title.

The couple is Nic (Annette Bening) and Jules (Julianne Moore), who are preparing for the impending college-bound departure of their daughter Joni (Mia Wasikowska). Joni's younger brother, the oddly named Laser (Josh Hutcherson), is pressuring her (as an 18-year-old) to inquire about their biological father's contact information. She concedes, and the two meet up with Paul (Mark Ruffalo), the hippie-ish owner of an organic restaurant.

All five members of the cast are good (and Bening and Moore have some stand-out moments), although none of these veteran actors are stretching their talents. The screenplay, by Lisa Cholodenko (also the director) and Stuart Blumberg, can't shake the sensation that the viewer is watching a film that's been written and crafted in a certain way. As a director, Chodolenko's smart enough to get out of the way and allow the actors to carry the weight.

The movie is a pleasant, sometimes funny, occasionally moving experience that never seriously falters, but never adds up to anything special. It's not good, it's not bad, it's just sort of all right.

Plus the soundtrack does not feature the Who song of the title.

Tuesday, January 4, 2011

Early Mann

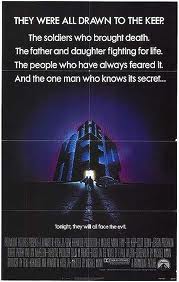

"The Keep" is the kind of film where unless you've read the book it was based on, you can forget about finding a narrative plot. It's based on a novel by noted horror writer F. Paul Wilson, the first in his six book Adversary cycle and the story probably makes more sense in book form. The book was a best seller so it makes perfect sense to turn out a motion picture. Michael Mann, fresh from 1981's "Thief", adapts the screenplay, assembles a cast that includes some very interesting actors, gets several million dollars from Paramount, and heads off to England. The end result holds together quite well for about twenty minutes, bringing the German Army (under the command of Captain Klaus Woermann, played by Jurgen Prochnow) to an isolated area in the Carpathian Alps of Romania, which consists of a village and a terrifying fortress called, simply, the Keep. Some foolish soldiers who really should pay more attention to the creepy-old-guy-who-looks-after-the-place start messing around looking for treasure and unwittingly release an evil force from its millennium-long imprisonment. This happens in a jaw-dropping sequence that appears to be a six-hundred foot tracking shot through mid-air. Then some special effects happen, and before you know it, the movie falls completely apart.

The movie ran over budget, Paramount stepped in, took final edit away from Mann and made the film incomprehensible. The SS (led by Major Erich Kaempffer, (Gabriel Byrne, in his motion picture debut) comes in due to the deaths of German soldiers blamed on rebels but actually the work of the creature. Then they bring in Dr. Cuza (Ian McKellen giving what maybe his worst performance ever) and his daughter Eva (Alberta Watson, the mother from "Spanking the Monkey".) Then a mystical warrior shows up, and it's Scott Glenn. He's inscrutable, he doesn't have a reflection, and he looks like he's been directed to act like he's on serious medication. He and Eva embark on a tantric sex thing before they've even really spoken to one another, and the good doctor is healed by the evil force, but he doesn't think it's an evil force. Plus, there's a priest in the village and he was a friend of the Cuzas, but then he isn't. Periodically, a very serious, intense argument will break out between characters that seem to be straining for some form of political or sociological weight, to no avail. Prochnow has several shouting matches with Byrne about why he hates totalitarianism, which I'll leave for the political scholars to puzzle their way through.

The two main adversaries of the piece are not mentioned by name until the last four minutes of the film, and even then only in passing and only once. There is no discipline, narrative or otherwise, which could possibly hold together the last seventy minutes of this film. Author Wilson was so disgusted with the end result that he wrote a short story, entitled "Cuts", about a horror writer who uses voodoo to kill a director who'd misadapted one of his stories.

And yet this film is never anything less than captivating. Part of this is due to the unique score by Tangerine Dream. It swirls, thuds, and suffuses the frame with an eerie, electric beauty that is quite suitably epic in tone. In addition to that, Cinematographer Alex Thomson is a genius with light, filling the anamorphic frame with an eerie and beautiful incandescence. There are several shots in this film that are quite breathtaking in terms of composition, lighting, and fear-laced beauty. The effects are a mixed bag, though since it's 1983, thankfully there is no CGI. The use of traveling mattes and reverse-fog is excellent, as are the five or six different ways that Nazis are shattered like china dolls. The excess of lasers at the end seems a little too disco and not as climactic as it doubtless was intended.

If Mann holds to his pattern of going back and recutting all of his films (which he has done for all of his features except "The Insider" and this one), perhaps one day we will see a version of "The Keep" that actually makes sense. But until then, a small but vocal internet cult will ensure that some people will find their way to "The Keep" every now and then. The film has not received a official DVD release but is currently available on Netflix streaming.

Sunday, January 2, 2011

Magic Bullet Theory

If you've only seen Edward G. Robinson in gangster films, give "Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet" (1940) a chance and see his range as an actor. Here he portrays German physician and researcher Paul Ehrlich, a pioneer at the turn of the 20th century in the treatment of infectious diseases and the man who found a cure for syphilis. Ehrlich starts out as a general practitioner employed by a hospital in order to provide a stable living for his family but whose real love is for research. His inquiring mind and nonconformist views ultimately makes him a leader in his field, but not before his pioneering ideas get him in trouble with the medical establishment in his country. Robinson has excellent support here with Ruth Gordon playing Ehrlich's adoring wife. Otto Kruger ably portrays Emil Adolf Von Behring, Ehrlich's friend and colleague who find himself at odds with his good friend's professional ideas at one point in their careers.

The film was controversial at the time for mentioning the disease "syphilis" by name, and I'm sure a little bit of sensationalism is why Jack Warner thought that Dr. Ehrlich's biography would be good material for a film, but there's something more subtle going on here. Made in 1940, after the Nazi menace had been recognized by many but before America had been attacked, there are many not so subtle digs at Germany to be found here. Early in the film several of Ehrlich's colleagues are ratting him out to the head of the hospital for not following hospital rules. Specifically, Ehrlich realizes that the sweat baths prescribed as the treatment of syphilis at the time - 1890 - are of no value whatsoever. When a patient of Ehrlich's says that the baths sap his strength and may cost him his job, Ehrlich says that he can skip the baths. This humane act of deviating from a useless treatment is the "rule" Ehrlich has broken, and what gets him called on the carpet by the head of the hospital. The whole incident is one of several that make the Germans look rigid and inhumane. The issue of Ehrlich's colleagues doubting his abilities because of his religion - he was Jewish - also comes up a few times. Finally, when the state budget committee that is financing Ehrlich's lab comes by for an inspection they chastise Ehrlich for hiring a "non-German" doctor. It's very effective but subtle criticism of the Germans that Warner Brothers did so well in the years leading up to the war.

One bone that Warner Brothers did have to throw to the censors because of the open discussion and showing of syphilis patients in various stages of the disease is that they could not show any female patients. They were only allowed to show male sufferers. I guess these guys all got this from "an inanimate object" as Dr. Ehrlich says is possible at one point in the film to downplay the sexual transmission angle of this disease.

The film was controversial at the time for mentioning the disease "syphilis" by name, and I'm sure a little bit of sensationalism is why Jack Warner thought that Dr. Ehrlich's biography would be good material for a film, but there's something more subtle going on here. Made in 1940, after the Nazi menace had been recognized by many but before America had been attacked, there are many not so subtle digs at Germany to be found here. Early in the film several of Ehrlich's colleagues are ratting him out to the head of the hospital for not following hospital rules. Specifically, Ehrlich realizes that the sweat baths prescribed as the treatment of syphilis at the time - 1890 - are of no value whatsoever. When a patient of Ehrlich's says that the baths sap his strength and may cost him his job, Ehrlich says that he can skip the baths. This humane act of deviating from a useless treatment is the "rule" Ehrlich has broken, and what gets him called on the carpet by the head of the hospital. The whole incident is one of several that make the Germans look rigid and inhumane. The issue of Ehrlich's colleagues doubting his abilities because of his religion - he was Jewish - also comes up a few times. Finally, when the state budget committee that is financing Ehrlich's lab comes by for an inspection they chastise Ehrlich for hiring a "non-German" doctor. It's very effective but subtle criticism of the Germans that Warner Brothers did so well in the years leading up to the war.

One bone that Warner Brothers did have to throw to the censors because of the open discussion and showing of syphilis patients in various stages of the disease is that they could not show any female patients. They were only allowed to show male sufferers. I guess these guys all got this from "an inanimate object" as Dr. Ehrlich says is possible at one point in the film to downplay the sexual transmission angle of this disease.

Saturday, January 1, 2011

Royally Tongue Tied

At it’s heart, director Tom Hooper's "The King’s Speech" is an old-fashioned buddy movie. The Duke of York, second son to King George V, is not expected to become king, and thankfully so, because he is afflicted with a stammer. On the other hand is Lionel Logue, an Australian immigrant and speech therapist, an eccentric who loves Shakespeare and has odd ideas about how to cure his patients.

The film bears all the trappings of a typical, Oscar-bait, Masterpiece Theater-type entertainment. It’s exceedingly British, with all the costumes and sets that that entails. We have locations like Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey, and Balmoral, along with the muted photography by Danny Cohen, perfectly represent the 1930s time period. But what raises the film above all this is the human emotion that bubbles to the surface thanks to a perceptive script by Danny Seidler, and two first-class performances from Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush.

Firth, who might as well compose his Oscar speech now, manages to navigate the tricky part by presenting the Duke as an underdog determined to rise to the challenge yet frightened that if he fails, the whole country could be lost to the charismatic Hitler.

Rush has an easier part, technically. He has all the good lines and Rush, given some shading by Seidler’s script, brings the man to life. We get a key scene when he auditions for Richard III at a local theater group and is basically insulted for being too old and too Australian.

The third piece in this film is Helena Bonham Carter as Elizabeth, the Duke's steadfast wife who was beloved by the public and is portrayed as the pinnacle of the British stiff upper-lip. the role maybe underdeveloped but Bonham Carter is eminently likable in the role.

Also making small but effective appearances are Michael Gambon as the old king, Derek Jacobi as the Archbishop of Canterbury and Guy Pearce as older brother David, the abdicated king, who is a largely reviled figure in history, but Pearce, along with the script, cuts him some slack (there are a few veiled references to his Nazi appeasement).

The film's climax is well known history but Hooper manages to invest the scene with a great deal of well-earned pathos.

The film bears all the trappings of a typical, Oscar-bait, Masterpiece Theater-type entertainment. It’s exceedingly British, with all the costumes and sets that that entails. We have locations like Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey, and Balmoral, along with the muted photography by Danny Cohen, perfectly represent the 1930s time period. But what raises the film above all this is the human emotion that bubbles to the surface thanks to a perceptive script by Danny Seidler, and two first-class performances from Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush.

Firth, who might as well compose his Oscar speech now, manages to navigate the tricky part by presenting the Duke as an underdog determined to rise to the challenge yet frightened that if he fails, the whole country could be lost to the charismatic Hitler.

Rush has an easier part, technically. He has all the good lines and Rush, given some shading by Seidler’s script, brings the man to life. We get a key scene when he auditions for Richard III at a local theater group and is basically insulted for being too old and too Australian.

The third piece in this film is Helena Bonham Carter as Elizabeth, the Duke's steadfast wife who was beloved by the public and is portrayed as the pinnacle of the British stiff upper-lip. the role maybe underdeveloped but Bonham Carter is eminently likable in the role.

Also making small but effective appearances are Michael Gambon as the old king, Derek Jacobi as the Archbishop of Canterbury and Guy Pearce as older brother David, the abdicated king, who is a largely reviled figure in history, but Pearce, along with the script, cuts him some slack (there are a few veiled references to his Nazi appeasement).

The film's climax is well known history but Hooper manages to invest the scene with a great deal of well-earned pathos.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)